Description

Notes and Editorial Reviews

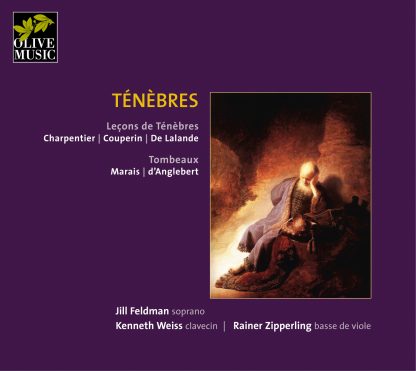

The notion of a program combining two forms of lament, one sacred, one secular, which fulfilled an important role in French Baroque music, is intelligent and intriguing. While a key component of both is their small scale—leçons de ténèbres were typically written for one or two solo voices and continuo, while the tombeau is invariably a solo instrumental work—they differ greatly in purpose. The tombeau represented a highly personal response to the death of a friend, or, as is the case in both examples included here, a revered teacher. In contrast, from the reign of Louis XIV ténèbres, settings taken from the first five chapters of the Lamentations of Jeremiah were public utterances of penitence that performed an important part of Holy Week liturgy, being performed originally at matins, but later as part of the afternoon devotions on the Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday.

Few French composers of note failed to make a contribution to the ténèbres tradition, the three examples included on the present disc representative of just some of the best known examples taken from an extensive repertoire. The earliest is that of Charpentier, taken from a cycle of nine leçons sung in 1680 at the convent of l’Abbaye aux Bois in Paris. It is also the most luxuriant of the three, richly embellished with melisma and ornamentation, and asking of its singer the ability to float pure lines of an almost sensual nature. These are requirements that suit Jill Feldman’s voice well. Feldman was one of the notable singers in the vanguard of the early-music revival; it is good to hear her again, and even better to find her voice, valued for its purity and sweetness, in such good shape. As with Emma Kirkby’s, it has not surprisingly filled out and darkened a little, but has also developed a slight edge. But it is perhaps the sheer musicality of her singing that impresses most, the use of color, the command with which ornaments are turned, and the response to words all indicative not only of an accomplished singer, but also one thoroughly experienced in this repertoire.

Couperin’s leçon is one of three composed for the Abbaye de Longchampt around 1713. Although it belongs to the same tradition as the Charpentier, there is rather less concentration on the florid, and more on capturing the mood of a text that includes the deeply felt and potent words of Jeremiah that form the opening verses of the first chapter of Lamentations. Some of its most moving moments are to be found in the settings of the Hebrew incipits (ALEPH etc.), exquisitely shaped melismatic vocalizes that incorporate some breathtaking modulations. Again, this is very much Feldman territory, but I’m slightly less convinced by her De Lalande, which asks rather different questions of the performer. Published in 1730 and composed for the Convent of the Assumption in Paris, it adopts a style closer to the motet, dropping the traditional Hebrew incipits (pace Catherine Cessac’s otherwise impeccable notes) in favor of strongly contrasted sections, and a flexibility of form in which the opening words (“Recordare, Domine”) are to be used as a refrain. The leçon includes several declamatory, récitative-like passages, and here there are times when the edge in Feldman’s voice becomes a little hard. But in general terms, all three performances are very rewarding.

The tombeaux are also given satisfying performances, the profoundly touching melody of D’Anglebert’s tribute to Chambonnières set in a swirl of improvisatory ornament-encrusted flourishes that make for rich effect on Kenneth Weiss’s copy of a Delin harpsichord of 1768. The Marais is perhaps given a less-accomplished performance than some I’ve heard, but Rainer Zipperling’s playing certainly doesn’t detract from a well-conceived and very well-executed program that can be confidently recommended to anyone attracted to the repertoire.

FANFARE: Brian Robins

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.